Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump recently accosted his fellow party opponent, former Florida Governor Jeb Bush, for addressing supporters in Spanish, playing to a controversial national issue that has long been settled in South Florida.

Thanks to our diverse Latino and Caribbean communities, particularly in Miami-Dade County, Spanish often functions as the primary language, and can be found from supermarkets to mom-and-pop establishments, and from large department stores to professional offices. This environment makes bilingualism a competitive trait – one would even argue a necessary one in South Florida’s labor market.

Naturally, the inability to communicate in both languages, whether for work or in daily life, can prove frustrating for English-Speaking Caribbean nationals here in South Florida. This frustration can inspire the xenophobic in us, the fear of cultures and languages different than ours.

There was a strain of this same fear when in 1980, a group called Citizens of Dade United proposed a ballot initiative making English the official language of the county. The move was in response to the renewed waves of immigrants during the 1970s and 1980s.

From 1981 to 1993, English was the official language in the county. The Dade County English Only Ordinance forbade the county government to fund programs not conducted in English or conducting business in any other language, and only few jobs required the bilingual criterion. However, as the county’s Latino community grew, so did the opposition to the ordinance. In 1993, following the redistricting of the county commission into 13 voting districts, voters gave the commission a Latino majority, which voted down the English-only ordinance.

The region is also undergoing another seismic shift, with now over 40 percent of South Florida population consists of migrants who speak languages other than English, with the majority speaking Spanish. This pattern repeats in other immigrant-strong states like New York, California, Texas, Arizona and Nevada. In response, Florida, Arizona and Texas also planned to submit bills for a national English-only bill. President Obama signed an executive order that made such initiatives unconstitutional, calling them “anti-American.”

And in many ways, such ordinances are truly “anti-American.” They are a hostile response to difference, to change. They are also born from a very human sense of insecurity among an unsure employment market. It would be so easy for English-speaking Caribbean-Americans – a minority within a minority – to lay their communication problems at the feet of an immigrant community demanding to keep their mother tongues on American soil.

This attitude, however, is fatal. It covers up the simple fact that Jamaicans have more in common with Cubans, and that Trinidadians have more in common with Venezuelans, than all do with what is considered a mainstream, English-speaking America. Among all countries sharing the Caribbean sea, we share a history and culture that runs far deeper than the European language we just so happen to be assigned to through some accident of colonialism. Here in South Florida, with no sea to separate us, we Caribbean-Americans, of whatever language, have a chance to be stronger than we ever were apart.

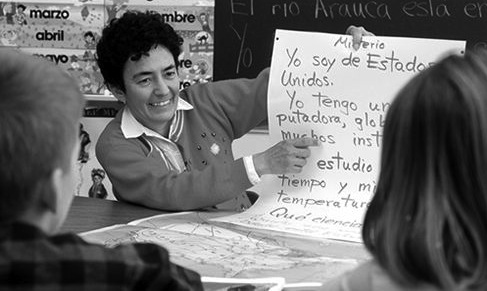

Instead of bemoaning these communication difficulties, we need to get proactive. The Caribbean-American Diaspora needs to get serious about bilingual education, making it a priority on our agenda. Caribbean-Americans, especially young people, need to learn Spanish in schools, colleges and elsewhere, to effectively compete on the job market, and communicate effectively with others. It’s also necessary for immigrants who are proficient in other languages to learn English.

Years of immigration has made America a starkly diverse nation of races and languages. It’s unlikely the nation will ever have an “English only” label. For the Caribbean-American’s sake, we may be made better for it.